It’s no secret that Iran provides critical support to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. The trouble comes in trying to figure out how much Iran spends and what that support actually looks like.

Estimates of Iran’s largesse vary considerably depending on who you ask, as my Bloomberg View colleague Eli Lake reported earlier this month. The United Nations’ special envoy for Syria, Staffan de Mistura, believes Iran spends about $6 billion annually propping up the Assad regime. Others believe that when you factor in Iran’s support for Hezbollah, which provides fighters to Assad, the number gets closer to $15 billion or $20 billion a year.

No matter the monetary total, a key component of Iran’s support for Assad is crude oil shipments. Syria once had a surplus of crude and even exported small amounts from its oil fields in the east. The civil war that broke out in 2011 has ravaged Syria’s crude production, which fell from about 400,000 barrels a day to roughly 20,000 barrels, according to recent estimates from the U.S. Department of Energy.

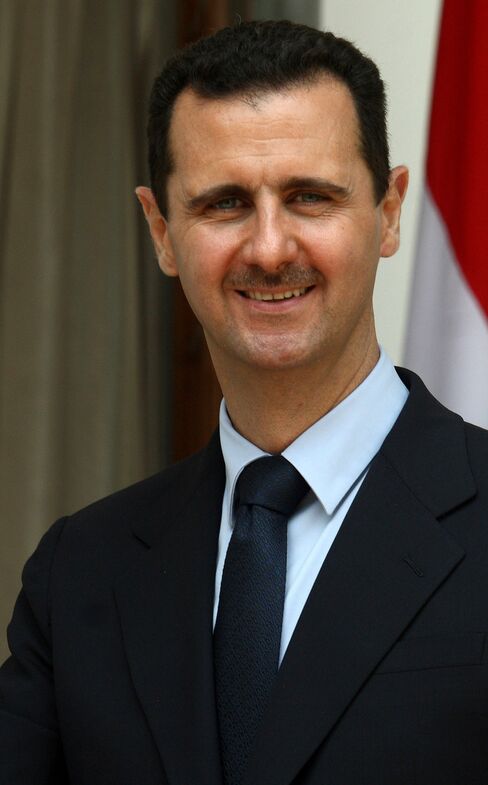

Syria's President Bashar Al-Assad.

Pankaj Nangia/Bloomberg

Last summer, meanwhile, the U.S. Department of State confirmed what many had suspected: Iran was helping to make up that shortfall by sending oil directly to Syria. The frequency of those shipments has remained largely unclear. New Bloomberg analysis of tanker movement suggests Iran has sent about 10 million barrels of crude to Syria so far this year—or about 60,000 barrels a day. With oil prices averaging $59 a barrel over the past six months, that’s about $600 million in aid since January.

So far this year, according to Bloomberg analysis, a total of 10 vessels have traveled from Iran to the Syrian port of Banias, which is still controlled by the Assad regime. The tankers appear to leave from one of two Iranian island ports, Kharg or Sirri, both in the Persian Gulf. The voyages last about two to three weeks and take the ships through the Strait of Hormuz, around the Arabian Peninsula, up the Red Sea, and through the Suez Canal.

Iran is using just three tankers to send oil to Syria, all of them classified as Suezmax tankers capable of hauling 1 million barrels each. These are the biggest class of ships that can get through the Suez Canal with a full load. The most recent delivery appears to have been made on May 26, when the tanker Amin delivered about 1 million barrels to Banias. A second ship, the Tour 2, arrived in Banias on June 16 and is currently anchored just offshore with an apparent delivery of crude. Below is a chart of the Tour 2’s route from Iran to Syria over the past month.

With most of Syria’s oil and gas producing regions controlled by either the Kurds or Islamic State, these crude shipments from Iran are vital to the Assad regime’s ability to hang on to power, says Andrew Tabler, a senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. This crude is likely being processed into fuel oil at the Banias refinery, he says, where it can be used for home heating oil, for power generation, and as fuel for what’s left of Assad’s military.

“Iran is basically fueling the entire country,” says Anthony Cordesman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. Cordesman and Tabler believe it’s unlikely that Syria is paying for this oil. Given the state of its economy after four years of intense civil war, and Assad’s dwindling currency reserves, it’s doubtful Syria has the money to pay.

By simply giving oil to Syria rather than charging for it, Iran is able to skirt U.S. and European Union sanctions designed to limit Iran’s crude exports. Under the sanctions regime imposed in mid-2012 as a penalty for its nuclear program, Iran is allowed to sell oil to only six countries: China, India, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Turkey. “This is just a blatant violation of U.S. sanctions,” says Mark Dubowitz, executive director of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies in Washington and a supporter of tougher sanctions. “It’s allowing Iran to fund Assad’s war machine with no repercussions.”

It’s not clear how the U.S. or Europe would go about stopping Iran from giving its oil to Syria. There’s no financial transactions to target, no money trail to follow, and no bank accounts to freeze. Peter Harrell spent two years working on sanctions at the State Department as the deputy assistant secretary for counter threat finance and sanctions. While he admits that Iran’s oil trade with Syria is “clearly a sanctionable activity,” he doesn’t see a practical way to end it. “You can’t simply turn this off by going after banks,” Harrell says. “You’d have to figure out how to physically stop the tankers.”

No comments:

Post a Comment